San Diego tribes launch effort to reduce the number of missing and murdered Indigenous people

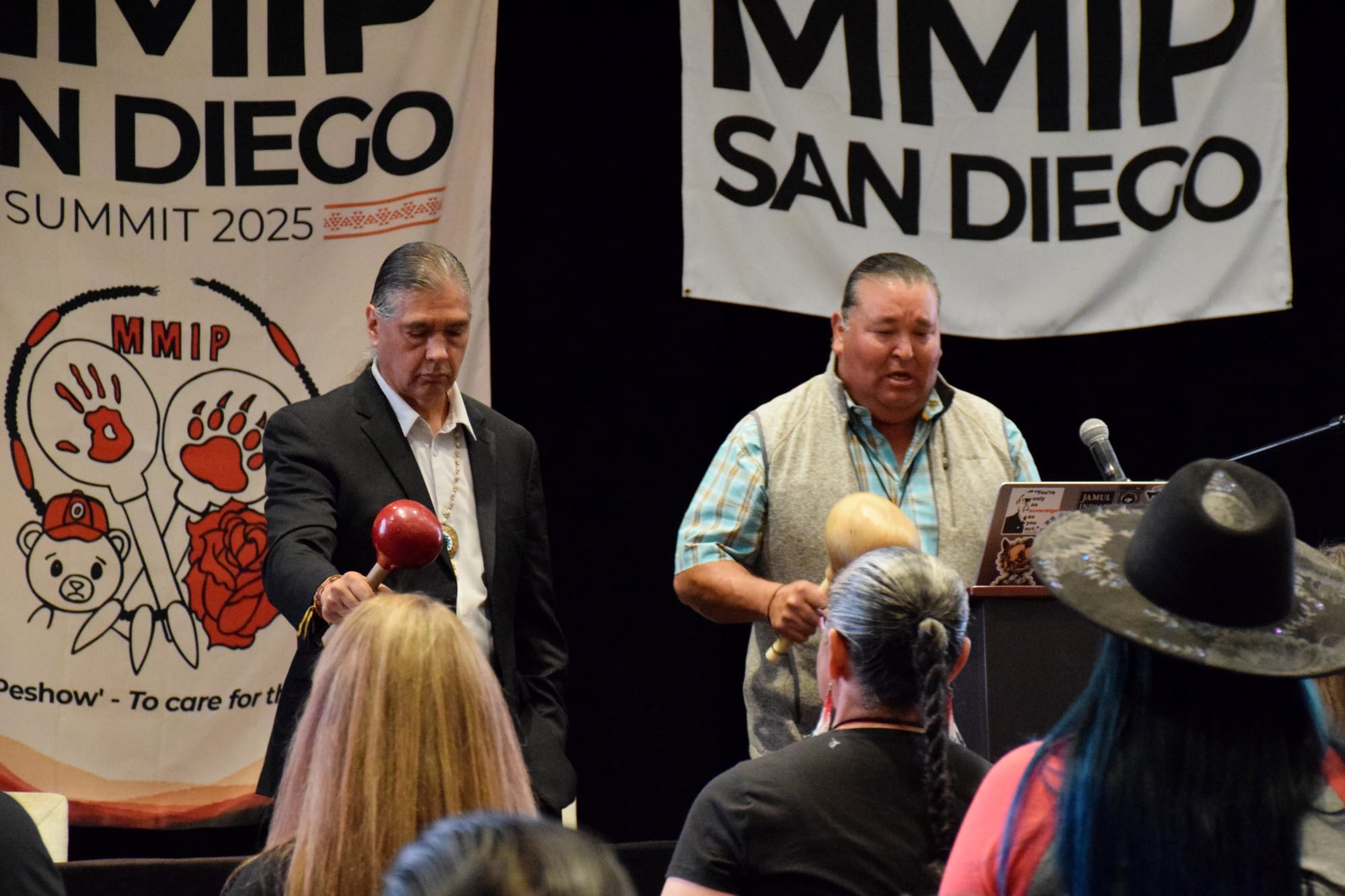

At an inaugural summit at Viejas Casino, organizers with the new nonprofit MMIP San Diego called for better collaboration between tribal, local and federal governments in the ongoing effort to reduce rates of violent crimes against Native people.

Written by Lauren J. Mapp, Edited by Kate Morrissey

Faced with disproportionately high rates of violence against Indigenous people, a coalition of Kumeyaay tribes in San Diego is joining forces to protect community members and prevent future tragedies.

The new nonprofit — MMIP San Diego — is raising awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous people, and working to reduce rates of violent crime against Native communities. It is a collaborative effort from the Jamul Indian Village of California, Manzanita Band of the Kumeyaay Nation, San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians, Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation and the San Diego Harbor Police Foundation.

On May 3, the organization held its inaugural Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Summit to raise awareness about violent crimes against Native community members.

“This summit reflects our deep tribal commitment to advocating for MMIP awareness, action and empowerment,” Sycuan Treasurer Brianna Scharnow said. “We must strengthen partnerships between tribal communities, law enforcement and all systems of support.”

Indigenous people in the United States experience murder, rape and violent crime at much higher rates than the national average, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

A National Institute of Justice study found that more than 1.5 million American Indian and Alaska Native women and 1.4 million men — or 84.3% and 81.6%, respectively — experience violent crime during their lifetime. The report also shows that 56.1% of Indigenous women and 27.5% of Indigenous men face sexual violence.

“Our perpetrators deserve to be brought to justice,” Jamul Chairwoman Erica Pinto said. “We deserve to be brought home once and for all.”

Held at Viejas Casino & Resort, the day included a session with local law enforcement officers about what to do if someone goes missing.

San Diego Sheriff Capt. Nathan Rowley dispelled the myth that loved ones need to wait 24 hours before reporting a missing loved one and said people shouldn’t feel embarrassed to call police.

“I'm here to say that time is of the essence,” he said. “You need to report early and be open and honest with the investigators. Every single minute that goes by takes away the chances for us to be able to recover those loved ones quickly and safely.”

Later in the day, Keelin Washington, assistant program director for Generate Hope, a nonprofit providing long-term residential programs for human trafficking survivors, emphasized the importance of educating communities about the true nature of trafficking. She said that it’s often misunderstood, and it's far more prevalent than people realize.

“When we think about trafficking, the first thing we think about is this girl who's kidnapped, right? Somebody in the white van kidnapped her,” Washington said. “But trafficking looks like somebody who comes alongside you and loves you and cares about you, at least initially.”

Human trafficking disproportionately impacts Indigenous communities, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

A study from the University of San Diego and Point Loma Nazarene University found that Native Americans are 3.5 times more likely to report being forced to have sex by “a violent pimp or partner.”

Washington, a survivor of trafficking, said she was only 14 when she met her trafficker in San Diego. Over the next four months, Washington experienced what she now knows was grooming — calculated acts of affection used to build trust and allowed her trafficker to manipulate and control her.

“He took me out of my safe place, he moved me out of the state of California,” Washington said. “He held all of my documentation, every dollar that was profited off of me, he kept. There was a lot of abuse. Then a lot of abuse ended up turning into torture.”

Recognizing the warning signs of manipulation and abuse in relationships is essential for eradicating trafficking, Washington said.

“For centuries, we've misidentified what trafficking actually is,” she said. “Millions of women and children never got justice, but today we sit in a time where laws have changed. We're not victimizing survivors of trafficking, we're providing them with resources.”

In recent years, with pushes from tribal members and leaders across the country, state and federal government officials have taken some steps to address rates of violent crimes against Indigenous community members.

In 2023, California launched its Feather Alert program to more rapidly respond to missing person cases for Indigenous people. The specialized alert is enacted when law enforcement agencies or tribes throughout the state believe an Indigenous person is endangered, suffering from a mental or physical disability, or vulnerable to human trafficking.

Last year, two Feather Alerts were issued in San Diego County, according to the Sheriff’s Department.

On April 30, 2024, the San Diego Sheriff’s Department posted an alert for Paula Connolly, a then 28-year-old from the Campo Indian Reservation, who was found safe the following week. On Oct. 18, an alert was posted for teenager Keira Trujillo from the Pala Indian Reservation, who was found safe in Las Vegas a week later.

During a press conference about the Feather Alert system in Sacramento last year, San Diego Sheriff Kelly Martinez said that law enforcement officers don’t generally have a good understanding of the dynamics in tribal communities. She said partnering with local tribes and promoting cross-cultural education is vital when it comes to reducing violence against Indigenous people.

“Tribal members don’t just live on reservations, they live in all of our communities,” Martinez said. “It’s important that other local law enforcement understand that when someone’s Indigenous, they need to be reported the right way so we can get them home safe.”

At the federal level, Savanna's Act, which requires the Department of Justice to provide law enforcement training related to missing and murdered Indigenous people, was signed into law in 2020. The law also requires that the department better educate the public on using the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System and report statistics on missing and murdered Indigenous people.

That same year, Congress passed the Not Invisible Act to create a joint commission to address violent crimes against Indigenous people across the country.

Nearly three years later in 2023 — and after holding seven hearings, during which 260 people provided testimony related to violent crimes in Native communities — that joint commission of tribal leaders, law enforcement officers, judges and survivors published a report of its findings.

The report said that there isn’t enough funding behind public safety efforts in Indigenous communities. The group also found that law enforcement needed to improve initial reporting of crimes and missing persons cases. To improve reporting, it suggested that the DOJ incentivize state, local and tribal governments to add their crime data in a national reporting system.

“Uniformity of guidelines across jurisdictions will result in more systematic and effective investigations and case resolutions,” the report says.

During the MMIP Summit earlier this month, San Diego Chief Deputy District Attorney Tracy Prior said these legislative changes and the actions they prompt give her hope that the justice system is finally starting to take the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people seriously.

“We all know that even one missing and murdered Indigenous person is too many,” Prior said. “Our common goals are to stop violence, to make victims safer, to hold perpetrators accountable and never let a single victim die in vain.”

Although he signed both the Not Invisible Act and Savanna’s Act into law during his first term, President Donald Trump's new administration has recently dealt significant blows to efforts to reduce violent crimes against Indigenous communities.

Within a month of stepping back into office, the Not Invisible Act Commission’s report was removed from the DOJ’s website, The Imprint reported. A copy of it is currently hosted on Turtle Talk, a blog covering legal analysis and legislation in Indian country.

The 2016 study on violence against Indigenous women and men from the National Institute of Justice was also removed soon after Trump’s inauguration, The 19th reported, but as of Monday, it was once again available on the institute's website.

Protecting Indigenous communities takes more than good intentions, Manzanita Chairwoman Angela Elliott-Santos said at the MMIP Summit. It requires support at all levels of government to pursue actions to keep people safe.

“As a mom and a grandma, one of the things I want to see happen is that our people have confidence, they learn self-defense, they learn to see the signs and that they have all the behavioral and mental health therapies that they need,” Elliott-Santos said.

“We just (need to provide) all people with that information and education to protect themselves so that we continue to be resilient and we don’t become victims.”