The quest for acceptance: Black creators and cosplayers fight for inclusivity at Comic-Con

While conventions and comic book publishing have become more diverse in recent years, there’s still more work to be done.

Written by Lauren J. Mapp, Edited by Maya Srikrishnan

With a regal air and flawless posture, James Powell strode through the exhibition floor at San Diego Comic-Con last month, looking every bit the part of a real knight.

Powell donned a set of armor, brandished a sword and wore his braided locs pulled to the back for his cosplay of one of King Lucero’s guards from S.G. Blaise’s “Hollow Healer” — a prequel to the “Lumenian” series, which the author describes as a blend of “Star Wars,” Lord of the Rings” and “The Princess Bride.”

Powell started as a superhero content creator, but over the past decade, he said he’s transformed cosplay into a full-time production career. In that time, he’s watched conventions become more inclusive for women and people of color — a shift he’s witnessed firsthand as more people attend the Black cosplayer meetups he hosts at Comic-Con and WonderCon each year.

“If you go back to maybe 2008 there weren't even really many women at the Con,” Powell said. “To watch everything move forward, and to watch the industry burst open with the kind of love and support that you don't necessarily see online — because that's where most of our pushback could come from — it's really great.”

For many Black cosplayers and comic book creators, gaining acceptance in pop-culture spaces like Comic-Con has required years of speaking up for themselves.

Some cosplayers have faced racist comments when dressed as characters who are typically drawn as or played by White actors. Meanwhile comic book creators continue to push publishers for better representation.

A decade ago, Newport Beach resident Anthony Bennett cosplayed at Comic-Con with his kids for the first time, a memory he still cherishes.

Dressed in “Black Panther” costumes — he and his son as members of the Border Tribe and his daughter as T'Challa’s younger sister Shuri — they merged with another group of people emulating the world of Wakanda. Photographers surrounded them, capturing the moment.

“Even with people who weren't of color, they understood the significance of it,” he said. “Just meeting other cosplayers that were dressed in Wakanda gear, and then people who just recognize you, it was just that type of moment. It was a true connection.”

Creating comics that reflect the range of Black experiences

While Black comic book characters like Lion Man, Black Panther and The Falcon have existed for decades, several creators at Comic-Con said they often failed to reflect the range of experiences in their communities.

Comic book creator Robert Roach launched Black Inc! Imprints in the early 2000s with his wife Yumi Roach to publish stories that reflected his own upbringing.

“T'Chaka is dead, T'Challa grew up without his dad. Luke Cage don't know who his daddy is. Jefferson Pierce, his daddy is killed,” he said. “All these Black fathers are absent in the lives of these Black men who became heroes, and that wasn't my experience.”

His “Menthu” series features strong relationships with both parents, set in present-day Los Angeles with nods to Egyptian mythology. Roach said he researched extensively to ensure authenticity, using Egyptian names in lieu of their more commonly used Greek counterparts like Anhur instead of Onuris

In illustrator and cartoonist Bianca Xunise’s fictionalized autobiography “Punk Rock Karaoke,” she spotlights the underground punk scene of Chicago’s South Side.

“The heart of the story is always going to be about punk, rock, goth culture, alternative culture,” she said. “That's what I'm writing stories about. These characters just happen to be people of color,” she said.

Creators also use comic books to teach important subjects that impact their communities.

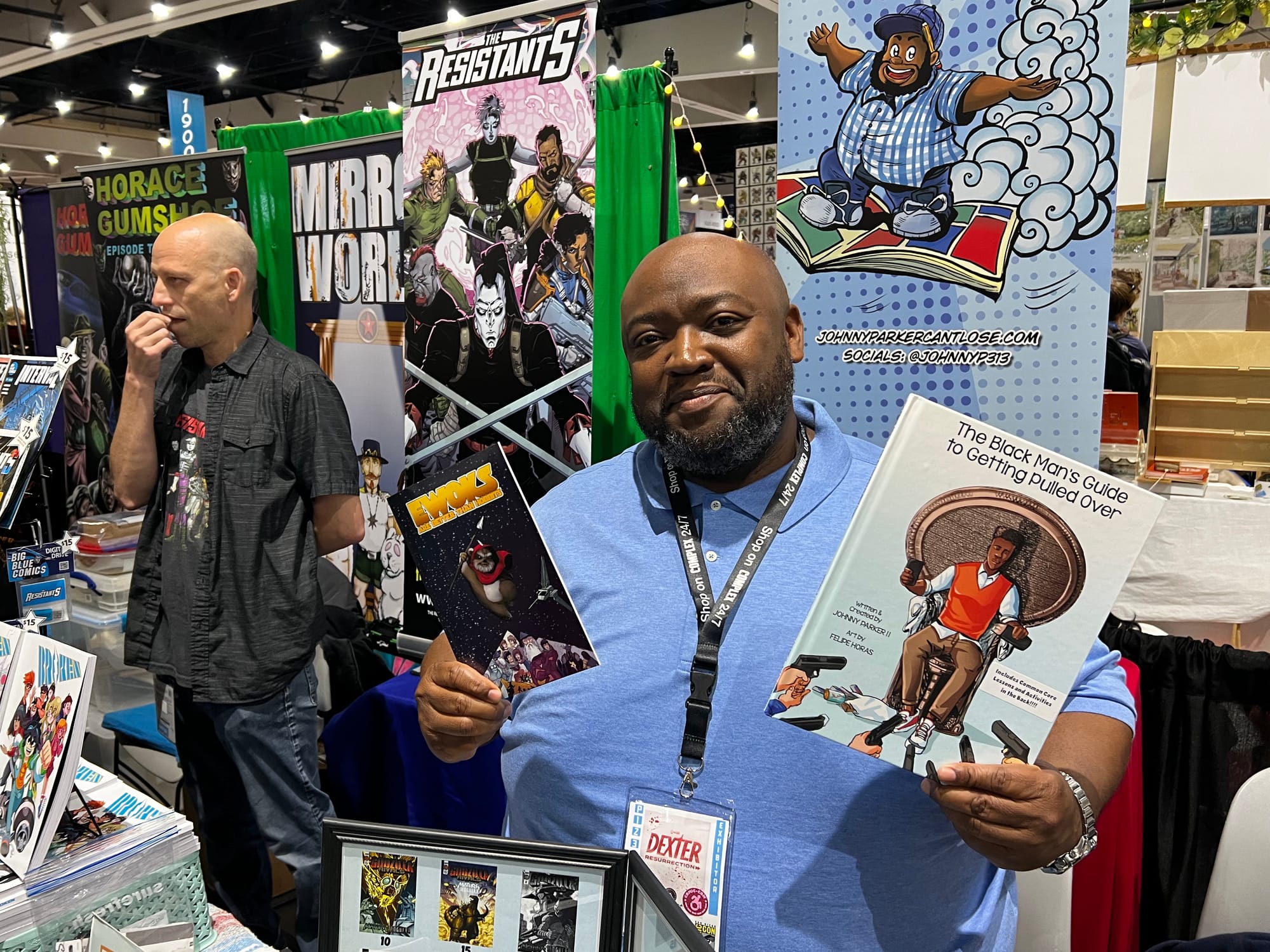

One example is “The Black Man’s Guide to Getting Pulled Over” by Los Angeles-based comic book creator Johnny Parker, which uses satire to confront the police harassment Black men face.

With a passion for reading fueled by comics — and inspiration from Black animator Dwayne McDuffie — he created his own comics after meeting an artist during an event at his local comic book shop. As a high school English teacher, Parker said books like his guide to facing police harassment demonstrate how comic books can serve as an educational tool.

“You can use comics in the classroom, just as you would with a novel, because you can do the exact same things,” Parker said. “You would analyze a novel for the vocabulary, the themes, the story, the plot. All these things can be done with comics as well.”

Building an even more inclusive pop culture scene

Comic book creators and cosplayers at Comic-Con said that while publishers have made big strides with inclusivity in recent years, more work remains.

Powell said that just last year, he dressed as Henry Cavill’s Superman and a White cosplayer made rude remarks to one of his friends.

“What I'll take with me, mostly, is that labels don't really mean anything to me,” Powell said. Cosplay is cosplay. Have fun doing what you're doing.”

While Roach said male characters of color have made big strides, in the future, he hopes to see better developed female characters. To achieve a more gender inclusive space, he said it’s especially up to men like himself to make space for women in the writers’ room.

Xunise agrees that achieving true inclusion in pop culture requires change at the top, with more Black and Brown producers deciding which properties to pick up.

“Just let us exist. Let us be in the room with y'all, especially in scenes like this where people are like, 'Oh, you can't cosplay as this character because they're not Black,'” Xunise said. “This is the world of play and fiction. It's like forever Halloween here. Let's just have fun.”