Imperial Beach cop watcher loses civil rights claim against sheriff's sergeant

The loss demonstrates how difficult it can be for people to sue officers for retaliation and prove it.

Written by Brittany Cruz-Fejeran, Edited by Lauren J. Mapp, Kate Morrissey and Maya Srikrishnan

A volunteer cop watcher from Imperial Beach lost a civil case last week where he and his lawyers accused a sheriff's sergeant of making up evidence to charge him with a felony in retaliation for his police accountability work.

After six days of arguments, a jury decided last Wednesday that Sgt. William Munsch did not violate the civil rights of Marcus Boyd, 58, during a 2022 confrontation that led to Munsch charging Boyd with a felony and keeping him in jail overnight. Boyd already won more than $500,000 in damages in an earlier decision about other issues related to the incident, including excessive force and false imprisonment.

It is difficult to prove retaliation by an officer and the outcome of this case demonstrates that.

Most jurors, like many members of the public, also tend to have implicit pro-police biases that they bring into the court.

Boyd said he was disappointed that the new jury didn’t see his side.

“Jurors have a hard time voting against police because they feel as though they're voting against their own safety,” he said.

Eugene Iredale, criminal and civil attorney with Iredale and Yoo, agreed.

“Very often the police are accorded the presumption of honesty and regularity that their actions really do not merit,” he said.

He said it can be a good thing for people to think highly of the police, but when a police misconduct case is brought into court, people have a hard time letting that implicit bias go.

An attorney for the county of San Diego who represented Munsch declined to comment on the verdict.

Boyd has lived in Imperial Beach since 2002. After watching video footage of police murdering George Floyd in 2020, he founded CopWatchers — a group of volunteers who film police interactions with the public and post videos on YouTube to hold officers accountable if they violate someone’s rights.

“The way I look at it, when you’re filming, the camera is the transparency, and the accountability is what we do with the video, in that it’s posted,” he said.

In June 2022, Boyd went to record sheriff's deputies responding to a domestic violence call in Imperial Beach. Boyd ended up in jail and charged with a felony after Munsch slapped his phone out of his hand.

A jury found in September 2024 that Munsch falsely imprisoned Boyd and used excessive force, but the members couldn’t agree on whether Munsch violated Boyd’s First Amendment rights.

Last week's proceeding asked a new jury to decide if Munsch made up evidence in retaliation for his cop watching, which would violate Boyd’s First Amendment rights. Boyd’s legal team argued that Munsch lied and charged him with a felony of assaulting an officer to keep him in jail for the night.

That night, after hearing about the domestic violence situation on a police scanner, Boyd arrived at the scene shortly after sheriff's deputies did.

In video footage Boyd recorded on his phone, Munsch walks up to Boyd and orders him to stay back from the scene. Boyd complies while also arguing with the sergeant. As they continue to argue, Munsch walks away from Boyd.

Then Boyd says, “That’s right. Keep walking.”

Munsch turns around to argue with Boyd again. Then he slaps Boyd’s phone out of his hand, knocking it into a nearby planter.

Boyd testified that he was petrified and shocked at that moment. He said he asked Munsch if he could pass the sergeant to retrieve his phone and asked for a supervisor. Then Munsch arrested him.

“That’s it. You’re done for the night,” Boyd told the court that Munsch said to him.

Munsch told the court his body camera was off during the interaction by mistake. He said he turned it back on after arresting Boyd.

After Munsch arrested Boyd and the other deputies had finished their domestic violence investigation, they regrouped to update each other and check the next calls they had to respond to. When the deputies huddled together, they all turned off their cameras at the same time at the mention of Boyd’s arrest. Munsch and his deputies said they turned off their cameras at the same time because their original investigation was over.

According to the San Diego Sheriff’s Department body-worn camera policy, “[cameras] shall be worn or used by uniformed personnel at all times during on duty hours in a law enforcement capacity, unless directed by a supervisor.” Munsch was a supervisor on the scene.

Munsch turned his body camera back on while transporting Boyd to the Sheriff’s office in Imperial Beach for booking. In body-worn camera footage from inside a holding cell, Munsch says he is charging Boyd with obstructing an officer.

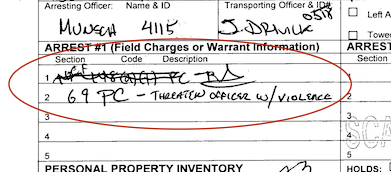

But Boyd said his booking slip showed a different charge, obstructing and threatening an officer with violence — a felony. The original misdemeanor charge was crossed out at the top.

Boyd didn’t find out until almost a year later while gathering evidence for the start of the trial that Munsch wrote in a report that Boyd “thrust his hand” in Munsch’s face, prompting Munsch to slap Boyd’s hand in self-defense.

The first jury decided that the thrust didn’t happen. Munsch still claims that it did.

Boyd said that for a Black man, assaulting an officer is like a death sentence. He said if he did assault Munsch, the interaction would’ve ended very differently.

“In my world, I know what would’ve happened. He would’ve killed me,” he said. “I’d be lucky to be alive.”

Black people in California are three times more likely to be killed by police than White people, according to Mapping Police Violence, a database that collects reports of police violence in the United States.

Munsch and his attorneys did not comment on this claim before publication.

Boyd's attorneys, Tim Scott and Lauren Mellano, with McKenzie Scott, pointed out that Munsch never told the other deputies on scene about the alleged assault, implying that he made it up later while filling out his report.

In court, Scott and Mellano argued that Munsch had arrested Boyd to get back at the CopWatchers for their work. Munsch denied arresting Boyd out of retaliation.

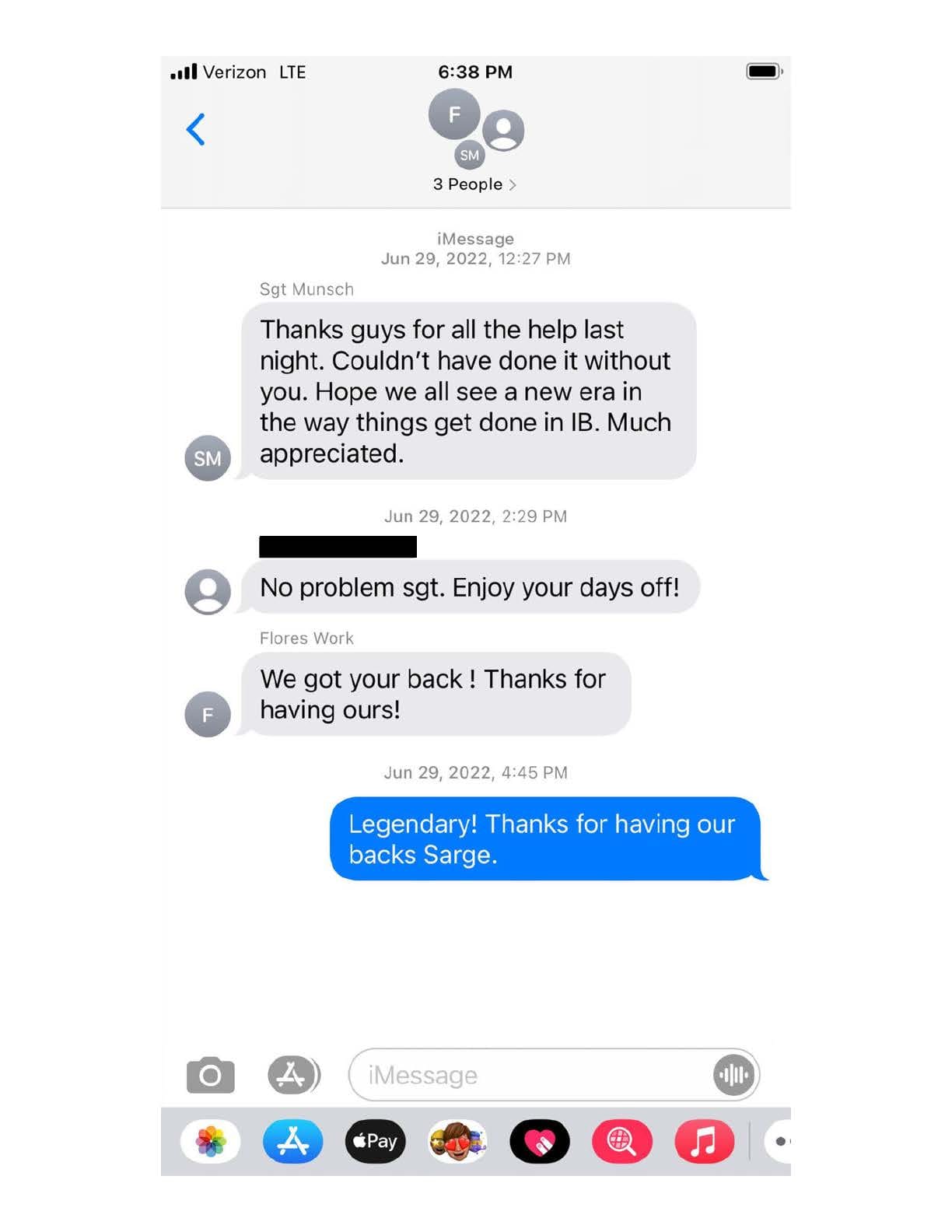

The day after the arrest, Munsch sent a text thanking the deputies on duty that night, calling it a “new era” for how things are done in Imperial Beach. Prior to the incident, Munsch also sent a text message about getting CopWatchers off their backs, referring to other volunteers who he claimed were harassing another officer.

Munsch said during the trial that he meant arresting Boyd for obstructing an officer would show the other deputies that they are also able to arrest CopWatchers volunteers if they impede an investigation.

In court, three deputies who were on the text thread denied knowing what the text meant and acknowledged that they already knew they could arrest people for obstruction.

In a previous testimony, Munsch also stated that a way to get CopWatchers off their backs was through more arrests.

Munsch’s attorney, Laura Wilson, repeatedly told the jury in her closing statement that the plaintiffs had no evidence to prove that Munsch made up evidence and retaliated against Boyd.

But that isn’t exactly true.

Without a direct confession, Scott and Mellano built the case from text message exchanges between Munsch and his deputies, body camera footage, lack of body camera footage and the fact that Munsch never told anyone about Boyd’s alleged assault on an officer at the time of the incident.

But Iredale said that proving someone’s intent is challenging because the only person who truly knows that person’s motive is the defendant.

The two types of evidence used in trials are direct evidence and circumstantial. Direct evidence is like a confession, whereas circumstantial evidence can come in the form of text messages or emails that imply what the plaintiff is accusing. Jurors were told that both kinds of evidence have equal weight.

In trials like this, proving intent often comes from circumstantial evidence, Iredale said, but people tend to trust it less than direct evidence.

The jury concluded that Munsch did act violently against Boyd, but did not intentionally interfere with his civil rights.

Scott said he hoped the outcome wouldn't discourage others from trying those kinds of cases.

Tasha Williamson, who is a friend of Boyd and attended the trial, said she encourages people harmed by law enforcement to file complaints and lawsuits against the departments.

“When [people] don’t, these departments are left to continue this behavior over and over again for generations without the public really knowing that these behaviors exist,” she said.

Boyd said he fears that sheriff's deputies will retaliate against him because of the case.

“I had some deep thought going home that I, you know, suddenly felt far less safe,” Boyd said. “As though they’ll probably be emboldened and feel as though that they could push me around a little bit more.”

He said he promised his daughter he wouldn’t cop watch at night anymore and he will make sure not to give officers a reason to arrest him.

“I’ll go silent, and I’ll drop to the ground before I stand my ground,” Boyd said. “If they push me, I will fall.”

But Boyd isn't done with court cases. He said he had dreams of becoming a paralegal. Watching his own case unfold inspired him to start taking classes at Southwestern College. He said he feels young again. He’s also developing an app that uses artificial intelligence to guide people through the process of filing civil violation claims if they’re unable to afford a lawyer.

“I want to help the little guy navigate civil rights violations,” Boyd said.