Trump expands fast-tracked deportations as ICE detains people outside San Diego courtrooms

Legal advocates say detention policies erode due process, turning attending hearings into a high-stakes trap.

Written by Marco Guajardo, Edited by Kate Morrissey

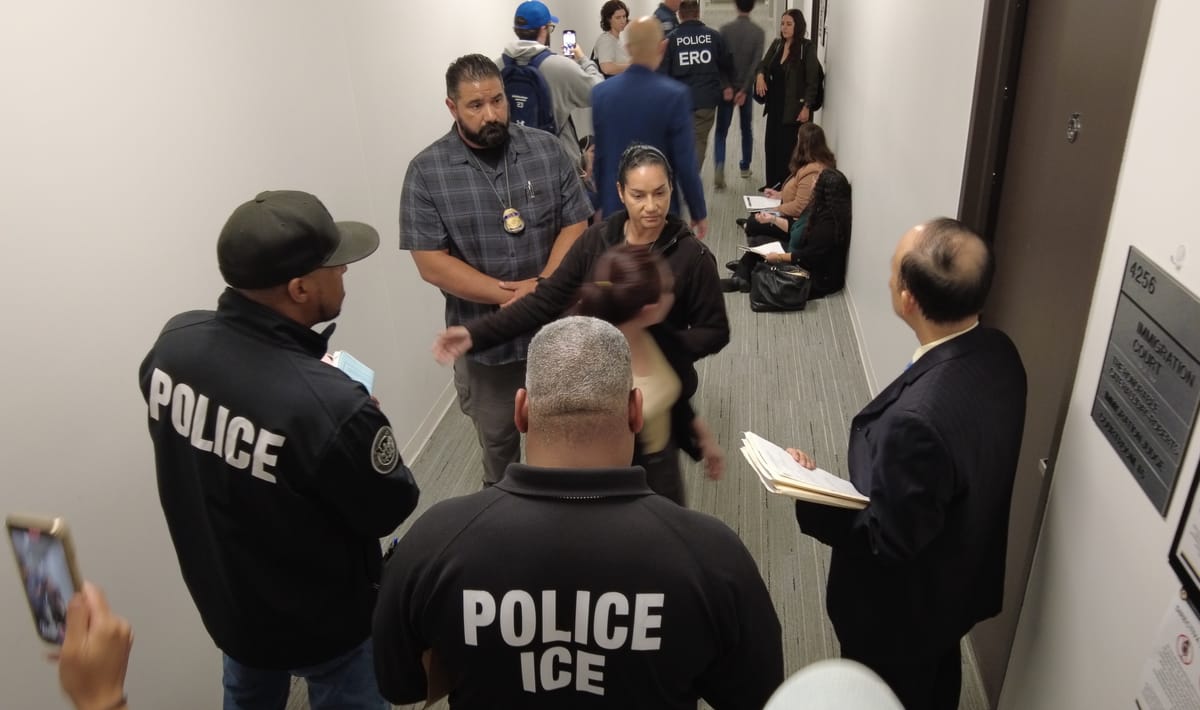

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers have arrested people in the hallways of the San Diego Immigration Court every day for more than two weeks in what advocates say is a coordinated effort to fast-track deportations and sidestep due process.

San Diego was among the first cities to witness ICE’s ongoing national operation of arresting people who show up for hearings in their immigration cases. Government attorneys are asking judges to dismiss the cases during these hearings, and then ICE officers detain the people as they leave the courtrooms.

Once the judges dismiss the cases, ICE places the people in a fast-track deportation process called expedited removal that allows immigration officers instead of judges to issue deportation orders for people who have been in the country for less than two years.

“They're not following due process procedures,” said Leslie Santos, an immigration attorney with Union Law Group. “They're not doing what normal asylum applicants are entitled to do in this country.”

In a January executive order, President Donald Trump expanded the use of expedited removal. Officials previously used the process for those caught without documents within 100 miles of the country's borders and with less than two weeks in the U.S., but now they can apply it to anyone in the country for less than two years.

ICE and the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which runs the immigration court, did not respond to requests for comment.

Ruth Mendez, a member of immigration advocacy group Detention Resistance, accompanied a friend to his morning hearing the first week of the operation.

Before the hearing started, Mendez walked with her friend to the restroom because he was concerned about the number of ICE officers standing in the hallway. When they stepped out, officers surrounded her friend, Mendez said.

Mendez told the officers that her friend hadn’t gone through his hearing yet, so they let him go, saying they wanted to speak to him after his hearing, she said.

Mendez said she overheard one officer tell another, “Don't let him escape.”

“Obviously, my friend was very, very nervous,” Mendez said. “He wanted to leave, but there was no way he could leave. At that point, everyone felt trapped.”

Mendez messaged advocates about ICE's presence at the court, and people from a variety of organizations responded.

The judge did not dismiss Mendez’ friend's case, but after his hearing, ICE officers took him into custody anyway.

Twice throughout the afternoon that same day, officers almost took someone into custody by mistake.

In one case, as an attorney argued with the officers about the legitimacy of an arrest, his client collapsed and began hyperventilating in what both the attorney and officers called a medical emergency.

The attorney pointed out that his client was not the man named in the warrant they had and eventually the officers released the man. The attorney put his client's arm over his shoulder and half-carried the man down the hallway to the elevators.

Attorney Santos went to court that day to represent a man from Venezuela. He had entered the country through an appointment at a port of entry made using a phone application called CBP One created under the Biden administration and ended by Trump.

Before entering the building, Santos spoke to a woman crying outside whose husband had come to the U.S. the same way and had been detained after his hearing, she said.

Santos stopped the government's attempt to dismiss her own client’s case. Santos advised her client to stay in the courtroom until it was empty.

Santos stayed in the hallway the rest of the day to advocate for other people who had hearings.

Several other attorneys made the same decision or came to help when word got out about what was happening.

After 4:30 p.m., Santos’ client walked out of the courtroom, and three ICE officers handcuffed him.

Santos flashed the client’s ongoing case documents to show he had another hearing, but the officers took him away.

Ginger Jacobs, immigration attorney at Jacobs & Schlesinger LLP, was one of the lawyers who came to the court to provide support.

By the end of the day, Jacobs said she had taken on four pro bono cases.

Many detainees have ended up in Otay Mesa Detention Center.

Valerie Sigamani, a local immigration attorney, said at a press conference Wednesday she recently visited three people held at the facility who were detained at the immigration court.

“People are afraid,” Sigamani said. “They come to this country believing that they are seeking safety for their families. I'm not quite sure if that's the truth anymore.”

The situations of those detained at the court vary, according to Sigamani. Some still have future court dates while others are facing fast-track deportation. Some are requesting screenings to show that they would be tortured if returned to their home countries, she said.

Sigamani said the U.S. Constitution guarantees people the right to not be arbitrarily detained and that the current policies resemble practices in other countries where people are detained without due process.

“This is a sanctuary of justice,” Sigamani said, pointing at the building that holds the immigration court, “and as of right now, it has been desecrated.”

Related Events:

June 28

Community March Against ICE: Fuerza Hispana de El Cajon, CA invites community members to protest ICE’s raids on immigrants in the city. The march will begin in the Manolo Farmers Market parking lot and continue to the El Cajon City Hall. 11 a.m. 1099 E Main St., El Cajon, CA 92021