After-school program reduces gang violence through mentorship, safe spaces and financial incentives

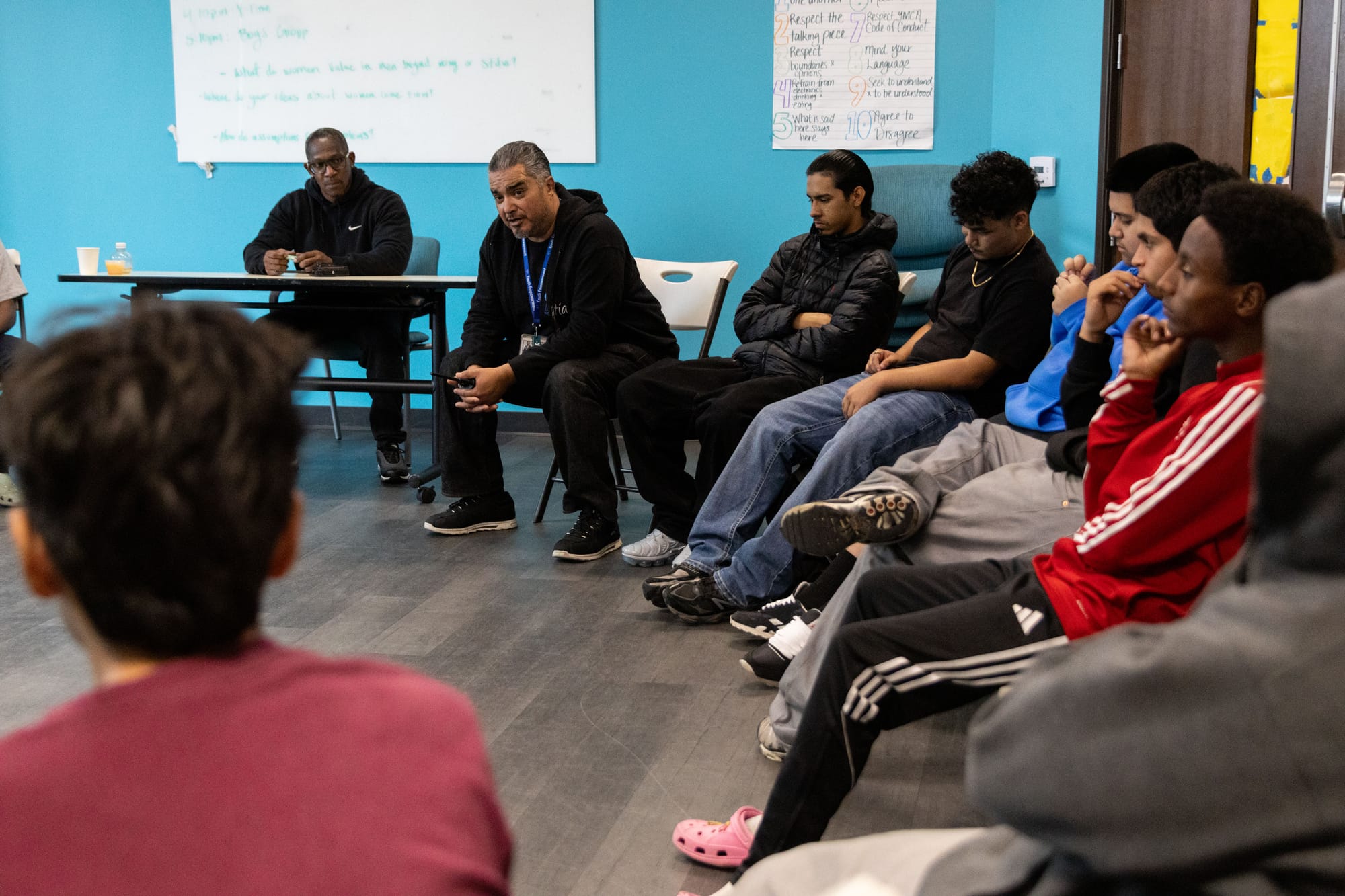

Youth Empowerment’s school program has helped reduce gang-related violence at Hoover High School since launching three years ago.

Written by Maya Srikrishnan, Edited by Lauren J. Mapp

In the last three months of 2025, Hoover High School saw no gang-related fights among students. That may be the norm at many high schools, but at Hoover, a day without violence among students has historically been rare.

The improvement was thanks to a partnership between the school and Youth Empowerment, a nonprofit organization that uses a community mentoring model to support youth in City Heights.

Youth Empowerment has run an after-school program for about three years with Hoover that targets youth already in the school-to-prison pipeline, or at risk of becoming a part of it.

In 2025, there were 133 fights on school property, said Michelle Wales, the organization’s director of school programs, but in the last three months of the year, there were none. The program faced a series of hurdles before it got to the point where it is now — a blueprint for restorative justice practices and violence prevention in schools impacted by gang violence.

Wales said initially when they started working with Hoover, they were called after altercations and other violent incidents had happened already, which made prevention difficult. But eventually they started working more closely with the school and students.

“Pretty much what we figured out is that there was 10% of the youth that were creating all the chaos in the school,” Wales said.

From there, the mentors worked on several peace treaties within the school between two rival gangs or situations between individuals that had escalated in order to ensure the school became a safe space. To this day, the mentors stop by the school during lunchtime daily to check in on the students in the program and chat with them.

The after-school program brought another round of challenges. Wales said she felt more like a nurse at first, because all the fighting kept them from actually starting the program.

“I was getting bandages, ice packs,” she said.

They worked with the youth to agree that the YMCA would become a neutral, safe space. Once they went outside, they could go back to their rivalries, but in the program space, it had to be different.

The students also receive money for participating in the program to deter them from trying to make money in ways that could get them in trouble.

“We figured if we're able to provide a safe place, put a little bit of money in their pocket, it would go a long way, because these kids are gonna find ways to make money, whether it's good or bad,” Wales said. “We figured that they don't have a safe place. We just have to assume that home life isn't safe. The parks aren't safe, just because of everything [that’s] happened. So we're able to provide a safe place.”

But there existed hurdles beyond the physical ones.

“It took deep diving within themselves,” Wales said. “So because the initial problem was the gang violence, they weren't seeing each other as kids. They were seeing each other as rivals.”

The peace treaties helped with that. But what made the biggest difference, she said, was a game of dodgeball.

Wales and the mentors had tried sports. But the students fought during soccer and tried to hit each other while throwing footballs. One day, another mentor suggested to her that instead of having the students play against each other, what if they played on the same team against the mentors?

“And so we did mentors against mentees,” she said. “That actually was the biggest game changer, because they thought that they were going to be able to pick sides and go against each other, but it wasn't that. We put them on the same team against us, and they started working together and playing together. And so in the moment of playing dodgeball, they forgot that they were enemies.”

From there the program has grown. They started with 30 students and now have 60 enrolled. While most of their work is at Hoover, they also have started connecting with Montgomery Middle School and Alba Community Day School.

Wales emphasized that all the mentors have lived experience similar to what the teens are going through, something she believes is essential to connecting with them.

“I went through a lot of sexual abuse that led me into drinking and starting drugs at a very young age,” Wales shared. “But that's because nobody thought to ask me, ‘Michelle, are you OK? What's going on?’

“All they said was, ‘Oh, well, Michelle, she's never gonna amount to anything. She's gonna be a drug addict.’ Well, a lot of these kids are hearing the same exact conversation.”

Youth Empowerment also realized that while they were making progress with the youth they worked with, that progress was slower if they didn’t work with the parents, too. The organization also runs reentry programs and a program for parents and guardians called “Parents on a Mission.” Often, adults in these programs will enroll their children in the school program.

Edgar Juarez, a parent whose son graduated from the school program and who participated in “Parents on a Mission,” said he initially doubted the program’s efficacy — and his son’s need for it.

“But the program really did not just change and impact my son,” he said. “It changed and impacted me, and that was just how we ended up more connected from a high school altercation.”

The parental program helped Juarez realize that his busy work schedule was preventing him from spending enough quality one-on-one time with his son. And the after-school program helped his son take control of his emotions and not let his anger escalate out of control. While in the program, he noticed his son recognizing when he would get mad and call his mentor.

Although Juarez and his son have both graduated, to this day, their bond is stronger because of the Youth Empowerment programs.

“I’ll say, ‘Hey, you got to de-escalate,’ or, ‘Hey, in this situation, you know, you didn't have a lot of control. Remember what you were taught,’” he said. “And he’ll point things out to me, ‘Okay, Dad, you've been pretty busy and I’d like to talk to you,’ and we’re both humble about it.”

Every day after school, mentors from Youth Empowerment meet students in their after-school program outside the doors of Hoover High School. One of the program’s first hurdles as it was developing was simply getting students safely from the doors of the school to the Copley-Price YMCA just a few blocks away, where the after-school program is held.

Initially one of the things they found was that students were getting jumped between exiting the school and walking to the YMCA, so the mentors decided to accompany them and try to prevent the violence. The mentors have stations along the path with walkie talkies, so they can keep students safe during the walk.

The program’s curriculum is slightly different each day of the week. It includes things like time to chill and do homework, as well as various discussion groups, including those separating the students by gender.

Students Michelle Guillen and Angela Ortiz met through the program — a friendship they expect will continue long past their graduation.

Ortiz, 17, came across the program through her boyfriend, who was also in it after being referred by probation. She had recently been kicked out of school and one day, while walking by the YMCA to see her boyfriend, the mentors encouraged her to join.

Guillen, 16, found out about the program through her brother after she had been getting into trouble.

“The thing that makes this program different is the one-on-one mentors,” Ortiz said. “We have a mentor specifically for us who I know I can be honest with.”

Ortiz said other programs she had participated in only had group discussions, which felt less comfortable.

Guillen and Ortiz said the program has helped them both communicate better with their families and friends, as well as introduced them to new experiences, like surfing, camping and kayaking.

“I think if you’re too scared to try it, you should anyway,” said Guillen, encouraging other students who have the opportunity to join.

Adrian Orozco, 15, joined the program a few months ago at his brother’s recommendation. The brothers don’t have the best home environment, Orozco said, and his brother told him how much the program helped him, so when he started Hoover as a freshman, he signed on. And he’s already seeing changes in himself.

“I’m kind of a hothead,” he said. “When I’m in a heated moment now, though, I can stop and think about multiple solutions to the situation.”

Youth Empowerment’s CEO Arthur Soriano grew up in City Heights. Soriano spent 23 years incarcerated. Upon release, he decided that he wanted a change.

“I once did harm in this community and now I’m bringing in resources,” Soriano said.

The nonprofit has faced some funding issues as many have under the second Trump administration.

It hit a speedbump last year with the federal government’s conflict over budget negotiations. But with the recent compromises over the budget, grant money that was earmarked by Rep. Sara Jacobs will come through to help continue funding Youth Empowerment’s after-school program.